I felt that it was a mistake to go downtown last Thursday, specifically to Shuk Maḥane Yehudah, but then again that was the day to go. It was the day before Sukkot started, and I needed to buy the "four species" that I would be needing for the holiday (well, three species actually ― dekel, hadassim, and etrog ― since it would have been foolhearty to buy aravot on Thursday afternoon for use on Sunday morning). And so did everyone else.

This certainly wasn't the only place to buy them, and this wasn't the only day, but as far as Jerusalem's population was concerned, it was probably the biggest on both counts.

"The atmosphere of the shuk." That's how my synagogue back in America, in 2001, described the sale of "four species" and decorations for the sukkah that would be taking place in the lobby, as a fundraiser for the youth group or something or other. (It was that year that I learned, slowly, that even though Orthodox seminary girls can be outgoing and chatty when selling you a poster for your sukkah, they don't like being flirted with in public under normal circumstances.)

"The atmosphere of the shuk." I don't know what the person was thinking who inserted that phrase in the advertisement for this special evening. They probably were not suggesting that there would be the atmosphere that I witnessed this past Thursday.

As for the actual atmosphere of the shuk, I don't get it. I mean: I do, but I don't want to. The coarse yelling, the bargaining, the aggressive children and teenagers who aren't professional salesmen, but who are doing this gig once a year as a moneymaker. There's such an atmosphere of competition in the air, you'd think we were at a sports bar. Why does anybody think this is the way it's supposed to be?

And yet I know I'm in the minority. I moved to Israel out of idealism about living in Israel, not out of idealism about living among Israelis. Most of the time I get by just fine, and my skin has grown a few inches thicker since I made aliyah in 2003, but sometimes the madness of it all just overcomes me.

I picked out my purchases and got exactly what I wanted, for a good price, without being a drain on the energy of the various salesmen involved. (There were no women on the job. See also: drivers, bus and taxi.) I didn't haggle for a better price, which was unexpected.

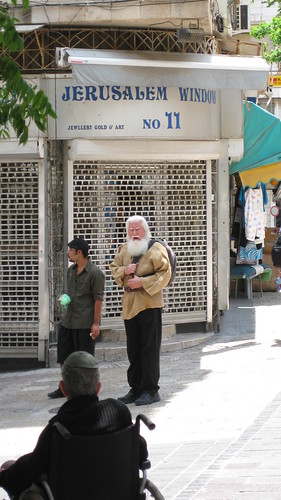

I could have been fine with all that, but what got me down particularly last week was the sense that there were substantially more beggars on the street. I used to be able to pinpoint the 10-12 consistent beggars on Jerusalem's main public spaces. Now they are so many more, just coming out of the woodwork. You couldn't stop on the street to look at something that caught your eye without being greeted with a "Shanah Tovah", which was nothing more than the perfunctorily greeting to draw your attention to their outstretched hand. (This, on the other hand, is an equal-opportunity occupation.)

Are these people in bad shape? I'm sure they are.

Do I give tsedakah? Yes, I do.

Do I know how to face every one of them with the response they deserve? No, I don't. It's just too much to face, and it seems to be growing.

Today, a week later, on the way to my job via the shuk, I was hit up again so many times. Buy something in a store and suddenly another customer appears at the counter, open change purse in hand, held up to me with no explanation. On the way down the street, a guy looking about 17 strolls over and asks me if I have any tsedakah for food. At the bus stop, a well-fed woman, sitting with her husband on the bench waiting for the bus, casually glances back at me asks me if I have any terumah to offer.

So I spend my day brokenhearted at what seems to be going on: the economic crisis of last year has left so many people underemployed that they've become that desperate.

That, and possibly also that the level of shame in begging has dropped to the point that the benefits to be gained outweigh it.

Is it a coincidence that the number of cheap-junk stores (i.e. the equivalent of dollar stores) seems to be growing?

I am amateurishly going to make a stab at the observation that Jerusalem needs more industry, something that would give a lot of jobs to a lot of people. Something that fits the prices of homes, for example. I'm also going to take a stab at the observation that a lot of the population is living on kollel stipends, and that that paradigm is simply not going to hold itself up since it, too, depends so much on charity-giving and the wide availability of cheap junk.

I made resolution to myself last Thursday to figure out some of this challenge and to try to overcome it. If I'm going to continue to live in the holy city, which is the plan, I've got to make sure not to be sucked into the downward spiral that so many apparently have.